- Contact details:

- luisa.jabbur@jic.ac.uk

- Part of

-

Biography

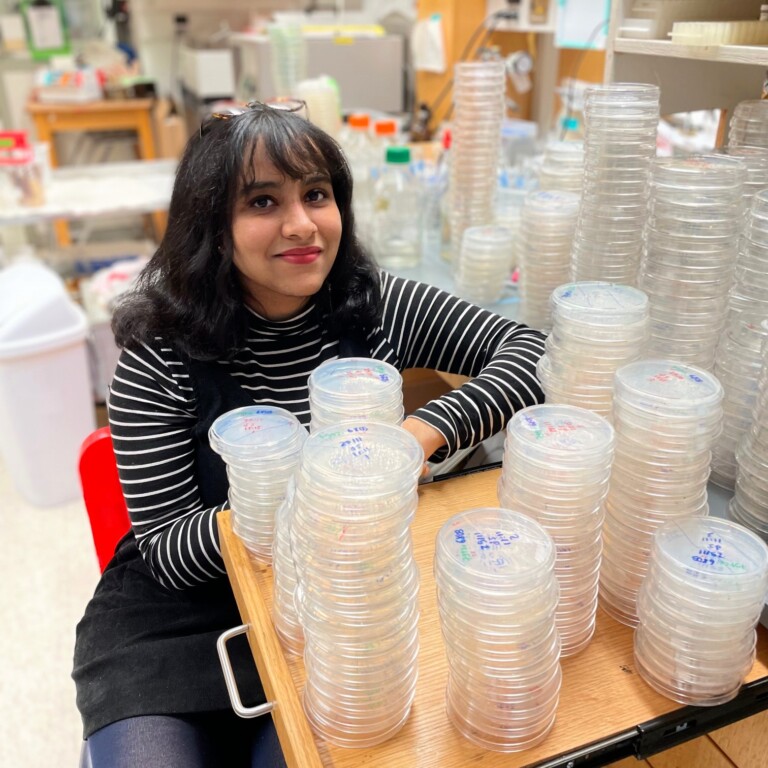

I am a microbial chronobiologist, but throughout the many years I have been in the field of circadian rhythms I have worked in a wide array of organisms, such as plants, fruit flies and humans, first as an undergraduate at the University of São Paulo (Brazil), then as a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan (US). I now focus my work on bacteria (in particular cyanobacteria) because I feel they offer us the best model organism to study the intersection between evolution/ecology and chronobiology.

Cyanobacteria are the oldest extant organism we know of, and they are incredibly widespread around the globe, occupying diverse niches. They also possess the most well-described circadian clock, with atomic-level resolution of its inner workings. During my PhD, which I did at Vanderbilt University (US) under the mentorship of Prof. Carl Johnson, I discovered that cyanobacteria are capable of anticipating the seasons by measuring the duration of the day and the night (what we call “photoperiod”). This ability, called “photoperiodism” had only been described in eukaryotes before, and this discovery opened up the possibility of using cyanobacteria as a model to understand both the underlying mechanisms and the past and future evolution of photoperiodic responses. Throughout the years, I have had the honour of being invited to present this work in many conferences and universities, and received awards from the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms, the European Biological Rhythms Society and the Center for Circadian Biology for this work.

Currently, I hold a BBSRC Discovery Fellowship with which I aim to expand upon the timely discovery I made during my PhD and establish cyanobacteria as a model for photoperiodism research, primarily answering three questions:

1) What are the mechanistic bases of photoperiodism in cyanobacteria?

2) How widespread is photoperiodism across cyanobacteria and prokaryotes in general?

3) How will photoperiodism evolve as a response to climate change?